|

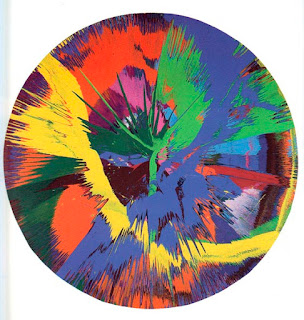

| Spin painting |

Damien Hirst has a mid-life retrospective at Tate Modern this summer. I was staying just across the river and could not resist wandering across. I had not seen his work in the original before (except for the diamond skull). My main impression was how very confident the work was. He seems to have been riding a wave throughout, relying on his ideas and intuitions rather than using or falling back on skill. Famously, he employs other people for the latter. But although this lack of physical engagement, and also the massive output, creates for me a certain vacuity and lack of substance, there was also a sense of movement and energy which was exciting because the work truly felt like a dynamic part of life rather a fossilized art work. I got the feeling that Hirst was too impatient to make anything much himself. Not his forte.

His very first spot painting, together with other student work, was shown in the first room. From the word go, it was all about simplicity and impact of the ordinary made dramatic. A row of brightly painted enamel saucepans hanging up - check. A set of cardboxes all different sizes and also brightly painted, as a corner installation - check. Untidy first spot painting discovered in Hirst's garage - check.

Much of his slightly later work was a deconstruction of the perfection and impersonality of minimalism (Judd, for example). Hence the glass cabinet containing rotting meat and breeding flies and dissected and preserved carcasses of dead animals. I liked the huge cabinets of drugs and medicines - these concerned not only Hirst's obsession with life and death, but also represented sort of anatomical diagrams, as they were arranged according to different body parts.

Later pieces (by which time artist had become extremely wealthy) tend to use much more opulent materials. I loved the vast cabinet filled with shelves of manufactured diamonds glittering fabulously against a mirrored or gold background. I did not visit the diamond skull, with its mockery of desire and wealth, again. Once was enough.